|

Back to Contents | |

|

|

||

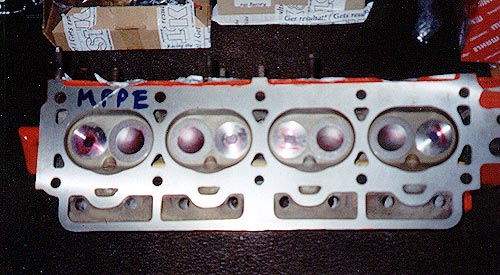

Phil Singher editor@vclassics.com As some of you will remember, I wrote the first article in what was to be a series about building a B20 street performance motor well over a year ago. I expected to document the entire project in three or four consecutive issues. That didn't happen. That first article is now so long gone that I'll just start over. Like many fans of old Volvos, I'd been on a quest for more power for years. At least, I'd been dreaming about it for years. In the summer of 2000, it looked like I finally had the resources, financial and otherwise, to get such a project "right." The first challenge was determining exactly what "right" was supposed to mean. The simplest approach was to build what I like to call "the IPD motor" (whether or not IPD supplies the actual parts), which has become a standard of a sort in the U.S. over the years. One takes a '74 or '75 B20F, overbores it to house B21 pistons, puts in an IPD Street Performance cam kit (Iskenderian VV71), has someone do a basic port and polish job on the head, has the motor balanced, and then installs it with medium-sized Weber side-draft carbs and an exhaust header. This results in 2130cc displacement and perhaps 150 HP at the flywheel if done properly, and less than stock performance if just bolted together without mods to the head. An excellent example is the motor Cameron Lovre has in his 122S Tancar. It's eminently driveable and the motor will pull hard from idle up into the 5000 RPM range. There are all sorts of variations on this theme, but it's a fairly safe approach; a known quantity. This costs roughly $5000 with proper machining and balancing. So, if I had $5000 to spend on a motor, did I really want to build one like that? That cam design is decades old, and I knew that in Europe, Sweden in particular, a lot of development has continued to take place. My friend David Hueppchen at OJ Rallye Automotive was marketing the Unitek&ST line of Swedish high-performance parts and building motors using those parts. We began discussing what a $5000 all-Swedish motor to suit my purposes would look like. The first step was to define what those purposes were. The new motor is for my '67 1800S, which is my daily driver. It would have to be reliable and easy to drive around town, get reasonable fuel economy at reasonable speeds (and less at unreasonable speeds), start every morning in all sorts of weather, and be happy cruising on long freeway trips. I already had a motor that does those things quite well, but I like chasing over mountain roads and more power would make that a whole lot more fun. I was also increasingly getting onto real race tracks, and the present motor is downright embarrassing in that environment. It's not fun to wave appliance-grade family cars by on the straights and then have them wallowing around the turns in front of me at unexciting speeds. And let's face it -- there's a vanity factor and bragging rights involved. High-performance motors are cool in their own right, and I wanted the coolest one I could get. Our first concept was to build something much like the IPD motor, only using modern Unitek&ST parts. David was to do the head work, and then we'd use the... er... well, which cam? Unitek&ST offers a wide range. And which header? David turned me over to Mike Aaro at Unitek for the definitive answers. I'd known Mike on and off for some years, and had always been impressed by his many years experience building street and race Volvo motors of all sorts. After we'd worked out which parts to use, David would supply them and advise me on how to put the motor together properly as the project progressed. In the months of three-way e-mails that followed, the concept grew. Mike insisted that some items David and I considered relatively unimportant in a street motor -- larger valves, for instance -- were worth the cost and effort. He also pushed for a bigger cam than we'd considered -- much bigger. I have no problem with having a rough idle, but how could it be possible to get low-RPM power from such a beast? The cam Mike wanted me to use was a lot hotter than the familiar Volvo "R" grind, and that doesn't really fire up until 3500 RPM or more. And were 45mm Webers really the minumum acceptable size? Mike prefered 48s, but I didn't have a lead on a pair of those. Years ago, I'd tried hot-rodding several Chevy V8 motors, and had ended up with over-cammed, over-carbureted, unstreetable messes that tended to self-destruct. I did not want to build a smaller version of those. Mike insisted his parts recommendations were what I needed. The important thing to understand is that a motor begins at the tip of the air intake and ends at the tip of the exhaust pipe, and if everything is physically tuned with the correct length and diameter, the motor can be tuned to be tractable at small throttle openings and low RPM while delivering all that much more power when opened up. Of course, the head would have to be modified in exactly the right way, or none of this would be possible. And as long as we were at it, why stick with a feeble 2130cc dispacement? Let's go for something bigger than that... What had begun as a medium-performance engine concept had now evolved into what we called the Multi-Purpose Performance Engine, because that's what it was -- a motor that would give excellent service for commuting, travel, sporty street driving and on the track. We've referred to it as the MPPE ever since.

I could already tell that my $5000 was not going to see such a motor to completion. It's not only the cost of the parts; precision machining is not cheap by any means, and we all agreed that excellent machining and balancing were crucial. I could perhaps stretch the budget a little bit, but the parts would have to be cheaper than anticipated. This led to another major shift in plans: the foreign exchange rate being very favorable to the U.S. dollar at the time, I could buy parts from Unitek&ST for less than I could domestically, even at discount rates. David then suggested I might just want to buy a head from Mike already built up. It took another six weeks to sort out all the details, but in early March 2001, I had my bank cable the equivalent of $3900 to Unitek&ST, and sent David another sum for a used set of Webers, the parts needed to rebuild them, the intake manifolds to mount them on, and all the hardware to make them all bolt up. Here's what we finally decided on for the motor's specs. There have been no changes to date.

Block

Head

Valvetrain

Intake

Exhaust

Ignition Other details could be worked out later, such as a light flywheel and stronger clutch*, electric cooling fan, fuel pump, etc. After placing the order, I casually asked Mike what sort of horsepower he projected. I had never set a target figure, knowing that HP alone tells you nothing about a motor's ability to accelerate -- HP determines the car's top speed, but acceleration is determined by how quickly a motor can rev up under load. Mike answered, equally casually, that it would surely be over 200 HP, with a very large torque figure I've since forgotten, and a very broad powerband. Now, that was truly startling because the long-held conventional wisdom in the U.S is that the limit for a street B20 is around 160 HP. Anything over that is a racing motor unworkable in regular driving. Most vintage racers struggle for anything much over 180 because the head casting limits the possible port shapes and sizes, and they're getting peak power around 8000 RPM, which the MPPE's bottom end isn't designed to tolerate. The few racers that can hit 200 HP are doing so after years of development, using expensive pistons and rods, and very high compression ratios requiring high-octane racing fuels. Those motors don't get at all happy until around 4000 RPM. And here was Mike saying, "Oh, over 200 HP for your daily driver, no problem. You will be putting it on a dyno for tuning, right? You'll see." The jury is still out on that until the engine is built and tuned, of course, but I recently had Boris Kort-Packard (122S autocrosser and mechanical engineering student) run all the MPPE specs through some "virtual dyno" computer software. This proves nothing, and I'm taking it with a large dose of salt, but here's a summary of what it spit out:

219.8 HP @ 7000 RPM (this is peak HP) That sure looks like a broad powerband to me! Even right from idle: the chart shows 127 ft/lbs @ 1500 RPM. The MPPE will supposedly make more torque right from idle than any stock B20 makes peak. If the reality is anywhere close to the projections, my coolness meter will be bending its peg.

What no one knew, Mike included, was that my order wouldn't leave Sweden for ten months. Such delays, I'm finding out, are not rare when dealing with performance building. The market for any particular part is tiny, and parts are produced as they are needed. When the outfit that supplies blanks for grinding cams doesn't supply them, cams like the one I'd ordered don't get made. The company that welds headers starts welding them so they don't fit, and that takes time to sort out. There's a sudden dearth of steel timing gears, so Mike can't lighten a set for me. New rod bolts can't be had for months. Normally, it would be possible to work around at least some of these delays by turning to other sources, but I'd placed a single order and had pre-paid for everything. After a period of increasing frustration, I finally decided to just let it ride. The parts would show up when they showed up. By the time the shipment finally did arrive (with all of $9 due to clear it through U.S. Customs), I'd become fully embroiled in after-hours computer work. The MPPE was costing a bit more than anticipated (which is always to be anticipated), but the resurrection of Marsha's 122S had, by then, sucked our Volvo projects fund dry. The money for all this had to come from somewhere, and I had no choice but to put the MPPE on hold while I earned some cash outright and tried to maneuver my career into something a bit more lucrative than it was. As that situation came under control this spring, I was finally able to devote some attention to the MPPE, at least the parts of it that were already paid for. I gave Cameron the head from the core motor for one of his own projects, he helped me haul the block from my garage into the Chamber of Horrors (he probably would have helped me even if I hadn't given him the head), and I set about disassembling the thing and cleaning all the parts that would be reused. Mike insisted that everything be "metrically clean," which approaches surgical cleanliness. Most shade-tree mechanics are happy enough to scrub the worst of the grime off using paint thinner or a similar solvent, but that's only the first step towards metric cleanliness. After that, parts go into a chemical dip for a day or two (I use Berryman's Carb and Parts cleaner -- the large size can will take anything smaller than a crankshaft), then they get scrubbed with a toothbrush in hot soapy water (a citrus-based detergent like Lemon Joy is the best), and those that show no trace of dirt or paint then get rinsed in more water and dried with a clean shop rag. Those with any remaining trace of crud go back into the dip for another day or two. This results in parts clean enough to inspect closely and measure accurately, and that will not introduce any abrasive dirt into a new, expensive motor. It's worth the trouble, even though it takes considerable time and elbow grease. Cameron gave me a spare rocker assembly, so I disassembled and cleaned two full sets (one of the great things about our local "unclub" is that whoever has a spare anything generally just gives it to whoever else needs it). Volvo rockers are rough castings with a few machined surfaces, and they are not at all uniform. A critical part of blueprinting a motor is to make all the valves operate identically, and the rockers are essential to that, so being able to match the best 8 from lot of 16 is advantageous. I may end up going through more, depending on how they measure out once mounted on the motor for testing, and then the best of the lot will be rebushed and resurfaced -- and then checked again. It's a big deal. I also dug into the Weber carbs. Note that this is not the popular "Weber carb conversion" used by people to replace worn-out SUs. These are serious, big side-draft units and they're intimidating to the uninitiated. I quickly got over this feeling. There are a whole lot of parts in each carb, but after a short tour through a manual, it's easy to understand what does what, how they come apart and go back together, and what will be involved in tuning later. They are now rebuilt. The next step in this area will be to test fit them on the 1800's present motor, work out the few missing linkage bits, and see if a good air box can be fitted without cutting parts of the car away. There are short manifolds available that will mount Webers with clearance to spare, but that defeats Mike's whole tuning concept. If we have to reshape the inner fender, so be it. The final thing I could do for free was finding a suitable machine shop, and this is a big factor in the project's success. While this is a street motor that uses pistons and rods not suitable for a dedicated 8000+ RPM race motor, I want it built with all the precision and care a race motor would get. This requires more than just doing some math, cutting away some metal and calling it good. It takes tinkering with, and some level of assembly, measuring, disassembly, and adjusting. I needed a place with both the skill and attitude to do the job right. After a long search, I'm sure I finally stumbled on the right place: Archie Somers Automotive Machine, no more than two miles from our house. It's a small shop that advertises only on the motors they build, which have large stickers on the valve covers that say "Somers Racing Engines" on them. Archie is a good listener who doesn't say much, but when he does, you're well-advised to pay attention. The MPPE is now in Archie's shop. The head is coming apart to have a mirror finish put on the exhaust ports (he liked the fine sandblast finish of the intakes just the way Mike supplied it) and will dowel the manifold mounting surface so the intake manifolds will line up to the ports with minimum fuss. I'd had Bob Moreno clean up the insides of the manifolds themselves, and now they're getting a finish to match Mike's intake ports. If I'm willing to spend the money to have this done right, Archie's happy. If I'm not in a hurry to get it out of there, he's not in a hurry to get it out of there. I didn't ask for an estimate -- at this point, whatever it takes is whatever it takes, and any scrimping would be a false economy. And that's where the MPPE project, revived at long last, currently sits. I'm working on further improvements to the 1800's suspension, and the original rear end with its tapered axles is about to become an issue with the amount of power projected to become available. There's a lot of detail work to be done to accomodate the new motor, but I hope to have it all running within two months. I'll leave you with a teaser. Cameron is now engaged in building a motor under John Parker's direction to take the high-end version of the Vintage Performance Developments supercharger kit. Bob Moreno is assembling the bottom end using forged pistons and reworking that old head from the MPPE core I gave Cam a while back, working to John's specs. This will end up in Cam's Tancar at roughly the same time the MPPE does in my 1800. Shootout at Portland International Raceway, anyone? *As we publish this, Vintage Performance Developments is supplying an aluminum flywheel and a special clutch disk for use with a regular Borg & Beck HD cover, supplied by RPR.

|